Risk Perceptions towards COVID-19 amongst the Adult Population in the City of Bulawayo, Zimbabwe: An Online Based Cross-Sectional Survey

Sandra V. Machiri 1 , Nyaradzai A. Katena 2 Portia Manangazira 3, Donewell Bangure 1 , Edwin Sibanda 4 , Sitshengisiwe Siziba 4 , Cherylyn Dumbura 5 , Evans Dewa 1 , Tinotenda Taruvinga 1 , Howard Nyika 1 , Nesisa Mpofu

1 Africa Centres for Diseases Control, 2 University of Zimbabwe, 3 Ministry of Health and Childcare, 4 Bulawayo City Council & 5 Zvitambo (Zimbabwe)

Abstract

Zimbabwe, like other countries, has not been spared by the COVID-19 pandemic. The government adopted the WHO strict behavioural measures to prevent the spread of COVID- 19. With the background that perception of health risk plays a key role in the adoption of recommended behavioural practices, this study was carried out to assess the risk perception towards COVID-19 and its determinants among adults in the city of Bulawayo in Zimbabwe. The study was an online based cross-sectional survey. Data was collected using a self- administered questionnaire which was uploaded on the Bulawayo City Council Facebook Platform.

A total of 256 participants responded and enrolled for the study. Ninety-two (92) percent of the participants perceived themselves to be at risk of COVID-19 infection, whilst 96% perceived that COVID-19 is a serious condition. The risk perception was significantly associated with age, place of residence and sex. Fifty-two percent of the participants perceived that adopting at least any one of the recommended protective behaviours is beneficial, whilst 22% perceived that there are some barriers that can hinder adoption of the recommended preventive measures.

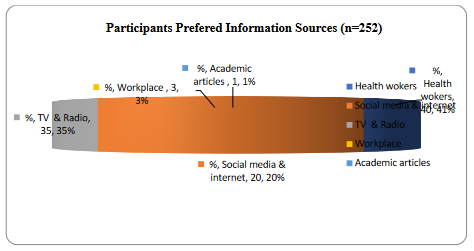

More than 50% of the participants mentioned that their preferred sources of COVID-19 information were the traditional media and health workers. Proper risk communication to promote protective behaviours using health workers and traditional media is thus very essential because these are the sources that the residents of Bulawayo trust. Keywords: COVID-19, risk perceptions, Bulawayo City, online cross-sectional survey

Introduction

The new Corona Virus (SARS-CoV-2) that has been named Corona Virus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) is a highly infectious disease that has led to the illness and deaths of people around the world. The first case was reported in the Hubei province of China on 29th December 2019 (Statista, 2021; Roser et al., 2020). The disease has been recognised as a global public health emergency by the World Health Organisation

Zimbabwe Journal of Health Sciences (ZJHS), Volume 1, Issue 1, December 2021

(WHO) on 11 March 2020. This was after cases had started to be seen outside China in less than two months. As of 4 March 2021, over 115 million people had been infected and 2.56 million deaths had been recorded in 216 countries and territories across all continents in the world (WHO, 2021). During the same period, the African continent recorded 3 915 304 cases and 104 398 deaths (Africa CDC, 2020).

COVID-19 is thought to spread mainly through close contact from person to person, including between people who are physically near each other (within about 6 feet). People who are infected but do not show symptoms can also spread the virus to others.

The virus that causes COVID-19 appears to spread more efficiently than influenza but not as efficiently as measles, which is among the most contagious viruses known to affect people.

This means that the primary focus for containing the novel Corona Virus outbreak is to prevent exposure through direct and close contact. The most effective way to control this type of spread is through good hygiene measures in community settings (hand washing, cough etiquette and staying home if sick) and strict infection prevention and control measures in health settings to prevent spread in hospital settings (WHO, 2021).

Nevertheless, the effectiveness of such measures depends on the public willingness to cooperate which, in turn, has been shown to be influenced by public risk perception regarding the pandemic (Lohiniva et al., 2020; Luo et al., 2020; Qian and Li, 2020; Wise et al., 2020). Risk perceptions refer to people’s intuitive evaluations of hazards that they are or might be exposed to including a multitude of undesirable effects that people associate with a specific cause (Rohrmann, 2008). Risk perceptions are interpretations of the world and the evaluation of risks is influenced by several individual and societal factors; and different social, cultural, and contextual factors influence risk perception. Different health education and psychological models indicate that risk perception is a key driver of behaviours (Mcleroy et al., 1988; Gorina, Limonero & Álvarez, 2018).

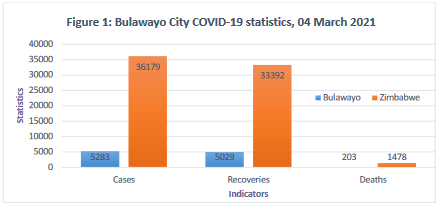

Zimbabwe has not been spared by the pandemic. The first case of COVID-19 in Zimbabwe was recorded on 21 March 2020. As of 4 March 2021, the country had recorded 36 179 and 1 478 fatalities (Zimbabwe: WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard, 2021). Majority of the COVID-19 cases and deaths have been experienced in the two largest cities of the country (i.e., Harare and Bulawayo) (Zimbabwe: WHO Corona Virus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard, 2021). Bulawayo, which is the second largest city, has contributed the second highest number of cases in the country. As of 4 March 2021, the COVID-19 statistics for the city were as shown in Figure 1:

Zimbabwe Journal of Health Sciences (ZJHS), Volume 1, Issue 1, December 2021

Figure 1: Bulawayo City COVID-19 statistics March 4, 2021

By 4 March 2021, the city had contributed 14.6% cases, 15% recoveries and 13.7% deaths to the national COVID-19 statistics. Despite the high number of COVID-19 positive cases and deaths in the city, some community members continued disregarding preventive measures especially in public places as evidenced by complacency in wearing masks, observing social distancing and washing of hands regularly (The Herald, 4 July 2020).

A survey of knowledge, attitudes and practices conducted in 2020 revealed a 90% knowledge levels of COVID-19 and its prevention. However, the complacency being observed was not an indication of behaviour change in line with the high knowledge levels that were noted. This could be because of low- risk perception. Several studies have shown that, despite having high knowledge about prevention strategies, people who perceived greater risk of COVID-19 infection are more likely to implement protective behaviours, and this reduces the probability of infection (Barrios & Hochberg, 2020; Cori et al., 2020).

On the other hand, people who perceive themselves to be at low risk of contracting a disease or condition were unlikely to adopt recommended protective behaviours. Consequently, sound empirical data on how lay persons perceive the risks of newly emerged COVID-19 is essential to devise proper risk communication strategies. Consequently, in light of this background, this study was carried out to assess the risk perception towards COVID- 19 and its determinants among adults in the city of Bulawayo in Zimbabwe.

Specifically, the study sought to:

Conceptual framework

Van der Linden (2017) recommends the inclusion of different variables that correspond to the cognitive tradition, for example, people’s knowledge and understanding about risks; the tradition, e.g., personal experience, the social-cultural paradigm; and relevant individual differences, e.g., gender, education and ideology. This “holistic” approach to modelling the determinants of risk perception prevents overreliance on a single paradigm, helps mitigate concerns about the questionable reliability of single-item constructs, and has also been adopted in recent studies of disease outbreaks (e.g., Prati & Pietrantoni 2016)

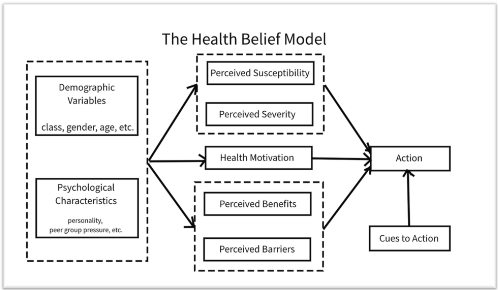

This study used the health belief model (HBM) shown in Figure 2 below as the conceptual framework.

Figure 2: The health belief model

Source: Mcleroy et al. (1988)

The HBM was developed so as to understand how people get to accept or reject a health behaviour or health service (Glanz et al., 2002). It is understood that individuals accept health messages better when they believe they are susceptible to a condition, feel at risk and believe that there is behaviour change benefits. In addition to beliefs, there is a need for one to be able to overcome the barriers to behaviour change.

Zimbabwe Journal of Health Sciences (ZJHS), Volume 1, Issue 1, December 2021

Study setting

This study was conducted in the City of Bulawayo in both the low- and high-density suburbs of the city. Bulawayo is the second largest city in Zimbabwe. It is located in the Matabeleland. It is considered as a metropolitan province which covers Bulawayo city and surrounding peri-urban areas. The City of Bulawayo has a total population of 753,337. Bulawayo City health department has health facilities that offer various health services to the communities. There are 19 clinics which include 4 that offer maternity services and 1 infectious disease hospital. The city is divided into 3 administrative districts, namely Nkulumane, Emakhandeni and Northern Suburbs.

Methods and materials

Study design and population

\An internet based descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted among adult residents, from 1 October 2020 to 31 January 2021. Adult residents with access to Bulawayo City’s social media platforms were included in the study. In this case, the Bulawayo City’s Facebook (FB) platform was used. The data collection tool was uploaded on the platform and those residents who were willing to participate would complete the questionnaire on the platform

Sample size and sampling procedures

A sample size of 256 was calculated using the Dobson’s formula for cross-sectional surveys. In terms of selection of participants, when the questionnaire was uploaded on the Bulawayo City FB platform, the City Public Relations Department put up an announcement on the same platform regarding the ongoing study. Adults who were free and willing would then log on and fill in the questionnaire on any day from 1 October 2020 until the sample size was reached on 31 January 2021. The youngest participant was aged 21, the oldest participant was aged 81 and the median age was 41 years. The rest of the characteristics of the study participants are shown in Table 1:

Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of respondents

| Characteristics | Frequency (n=254) | Proportion |

|---|---|---|

|

Sex: Male Female Not specified Neutral |

102 146 6 1 |

40.1% 57.2% 2.3% 0.4% |

|

Age Group: 20-29 30-39 40-49 50-59 60+ |

34 96 54 45 16 |

13.7% 38.7% 23.0% 18.1% 6.5% |

|

Marital Status: Single Married Cohabiting Divorced Widowed Not specified |

89 144 7 5 7 2 |

35.0% 56.7% 2.8% 1.9% 2.8% 0.8% |

|

Highest level of Education: None Secondary Tertiary |

5 27 222 |

2.0% 10.6% 87.4% |

|

Area of Residence Low Density High Density Unspecified |

119 127 8 |

46.9% 50.0% 3.1% |

|

Employment status: Unemployed Formally employed Informally employed |

24 198 41 |

9.5% 74.4% 16.1% |

|

Religion: Catholic Protestant Apostolic Faith Pentecostal Muslim Afrivan tradition None |

44 96 12 73 2 11 16 |

17.3% 37.8% 4.7% 28.7% 0.8% 4.4% 6.3% |

Data collection tools and procedures

Data were collected using a self-administered questionnaire which was uploaded on the Bulawayo City Facebook platform in a digital survey form. The questionnaire was designed based on the constructs of the Health Belief Model. The questionnaire was pretested at one of the City Health facilities before being uploaded on the FB page. Data from the pre-test were excluded from the final analysis. The questionnaire had two sections: Section A - socio-demographic characteristics; and, Section B - perceptions towards COVID-19. Section B also contained questions about participants’ preferred sources of information since these serve as cues to action. Questions on participants’ perceptions towards COVID-19 were measured on a five- point Likert scale which ranged from strongly disagree to strongly agree.

Data management and analysis

Data was entered and analysed using Microsoft Excel and Stata. The analysis was mostly descriptive. In addition, Chi-square tests were calculated in order to assess the association between risk perception and area of residents (low-density and high- density suburbs)

Ethical issues

The Bulawayo City Health Department Ethics Committee reviewed the proposal before uploading of the questionnaire on the FB platform. Additionally, participants filled in the questionnaire anonymously.

Results

Two hundred and fifty-six (256) participants enrolled for the study. Out of these, 2 questionnaires were totally excluded from the analysis due to incomplete data. The study thus had a 99.2% response rate. However, some of the questions had a few missing responses and these were analysed using the available responses. Therefore, there were less than 254 responses in some questions. To this end, the total number of responses would be specified for each question.

Perceptions towards COVID-19

Majority of the participants either strongly agreed or agreed that they were at risk of getting COVID-19. Majority also strongly agreed and agreed that COVID-19 is a serious condition. Nevertheless, there were a significant proportion of participants who perceived that there were some barriers to adoption of the recommended COVID-19 practice. The barrier that was mentioned by majority of the participants was that using hand sanitisers can cause skin reactions. Table 2 shows the responses of participants on different perceptions towards COVID-19

Zimbabwe Journal of Health Sciences (ZJHS), Volume 1, Issue 1, December 2021

Table 2: Participants responses on perceptions towards COVID-19

| Questions | n | Responses | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SA | A | N | D | SD | ||

| A: Perceived Susceptibility: I am at risk of getting COVID-19 | 252 | 157 (62) | 76 (30.6) | 17 (6.8) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) |

| If I am in contact with someone who has tested positive, I am at a higher risk | 254 | 193 (76) | 49 (19.3 | 8 (3.1) | 2 (0.8) | 2 (0.8) |

| I can have COVID-19 with no sign and symptoms | 254 | 163 63.9) | 74 (29.2) | 12 (4.8) | 5 (2.1) | 0 |

| Going to crowded places like markets increases my risk of infection | 254 | 206 (81) | 44 (17.4) | 2 (0.8) | 2 (0.9) | 0 |

| Going to crowded places like funerals increases my risk of infection | 253 | 196 (77.5) | 54 (2.3) | 2 (0.8) | 1 (0.4) | 0 |

| Not wearing my mask properly in crowded places increase my risk of infection. | 254 | 210 (82.4) | 39 (15.3) | 4 (1.6) | 1 (0.4) | 0 |

| Perceived Severity: | ||||||

| COVID-19 is a serious disease. | 253 | 191 (75) | 52 (21.2) | 7 (2.8) | 2 (0.8) | 1 (0.4) |

| COVID-19 spreads fast. | 253 | 191 (75) | 52 (21.2 | 7 (2.8) | 2 (0.8) | 1 (0.4) |

| There is no treatment specific for COVID- 19. | 254 | 153 (60) | 73 (28.6) | 15 (5.9) | 2 (0.8) | 0 |

| Being infected by COVID-19 can lead to complications | 254 | 154 (60) | 80 (31.5 | 13 (5.9) | 7 (2.8) | 0 |

| Being infected by COVID-19 can lead to death. | 254 | 148 (58) | 71 (27.8) | 20 (7.8) | 12 (4.7) | 3 (1.2) |

| Perceived Benefits: | ||||||

| Washing of hands at all times with soap and water or a sanitiser protects me from COVID-19 | 254 | 133 (52.4) | 99 (38.3 | 16 (6.4) | 3 (1.2) | 3 (1.2) |

| Maintaining social distancing in public places protects me from COVID-19 | 254 | 146 (57.5) | 88 (34.7) | 14 (5.5) | 2 (0.8) | 4 (1.5) |

| Coughing on the inside of my elbow prevents the spread of the virus. | 253 | 113 (44.7) | 110 (39.5) | 28 (11.1 | 5 (2.0) | 6 (2.4) |

| Perceived Barriers: | ||||||

| If I wear my mask, I feel uncomfortably hot | 253 | 58 (22.9) | 128 (50.1) | 29 (11.5) | 27 (10.7) | 10 (3.9) |

| If I wear my mask, I am not able to breathe well. | 253 | 28 (11.8) | 98 (38.5) | 54 (21.0) | 57 (22.5) | 16 (6.1) |

| Washing my hands all the time makes them dry and chipped. | 253 | 17 (6.7) | 57 (22.6) | 52 (20.7) | 90 (35.7) | 36 (14.3) |

| I have no access to water for washing my hands. | 254 | 38 (15) | 58 (22.8) | 36 (14.2) | 82 (32.2) | 40 (15.8) |

| It is difficult to stand 1 metre apart in public spaces | 254 | 66 (26) | 82 (32.3) | 23 (9.1) | 50 (19.7) | 33 (13) |

| I have no access to soap to use for hand washing | 254 | 11 (4.4) | 26 (10.3) | 28 (11.1) | 129 (51) | 59 (23.3) |

| Using hand sanitisers makes my skin react | 253 | 10 (4) | 41 (16) | 47 (18.9) | 109 (43.1) | 46 (18.2) |

Knowledge of COVID-19

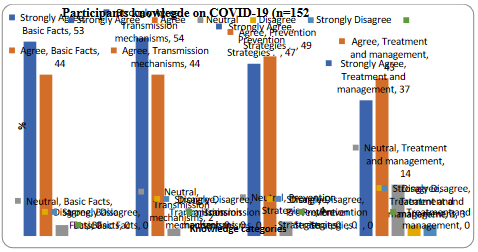

Majority of the participants had knowledge of COVID-19 basic facts, transmission mechanisms and prevention strategies. About 17% indicated that they did not have knowledge of management and treatment of the condition as shown in Figure 2:

Zimbabwe Journal of Health Sciences (ZJHS), Volume 1, Issue 1, December 2021

Figure 2: Participants’ knowledge of different aspect of COVID-19

Current and preferred information sources

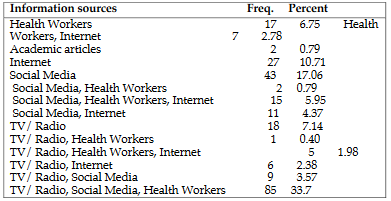

Participants’ responses about their current and preferred information sources are shown in Table 3 and Figure 3 respectively

Table 3: Respondents' current sources of COVID-19 Information

Zimbabwe Journal of Health Sciences (ZJHS), Volume 1, Issue 1, December 2021

Figure 3: Respondents' preferred sources of COVID-19 information

Association between perceived risk of COVID-19 and socio-demographic variable

There was an association between perceived risk and age-group, sex and place of residence as shown in Table 4 below:

Table 4: Association between Risk perception and socio-demographic variables

| Variable | Pearson Chi-square | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Level of education | 4.7 | 0.78 |

| Age group | 51 | 0.00 |

| Sex | 72.1 | 0.003 |

| Place of residence | 40.4 | 0.004 |

Discussion

The aim of this study was to assess the risk perception towards COVID-19 among adult residents of Bulawayo City. This was informed with the background that the number of cases of COVID-19 continues to increase in the City of Bulawayo as people were not adhering to the WHO recommended preventive measures. According to (Dryhurst et al., 2020), disease spread is influenced by people’s willingness to adopt preventative public health behaviours, which are often associated with public risk perception. Therefore, it was of paramount importance to carry out this study in order

Zimbabwe Journal of Health Sciences (ZJHS), Volume 1, Issue 1, December 2021

to gather evidence that would assist in improving the ongoing COVID-19 interventions.

In terms of perceptions towards COVID-19, i.e., perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, and perceived barriers and benefits of adopting recommended preventative measures, this study found out that the majority of participants either strongly agreed or agreed that they were at risk of getting COVID-19. The majority also strongly agreed and agreed that COVID-19 is a serious disease, but there were a significant proportion of participants who perceived that there were some barriers to adoption of the recommended COVID-19 practice. These findings are consistent with findings from Ethiopia (Asefa et al., 2020, Motta Zanin et al., 2020) and Germany (Gerhold, 2020).

The high perception of risk is not surprising since the majority of participants indicated that they had knowledge about the basic facts and transmission of COVID- 19. As postulated by several behaviour change experts, risk perception is a product of knowledge of the disease in question as well as other factors (Mcleroy et al., 1988). It may also mean that people who perceive high risk of COVID-19 are more likely to seek knowledge about the condition in order to prevent themselves from being infected. However, due to the cross-sectional nature of the study, one could not ascertain the temporal relationship between risk perception and having knowledge. Nevertheless, high risk perception among participants who have knowledge about COVID-19 was also previously reported in studies in Ethiopia (Asefa et al., 2020) and China (Kwok et al., 2020).

It was also interesting to find out that the majority of participants preferred to obtain information about COVID-19 from health workers, radio and TV, with social media being relatively lowly preferred. These findings are congruent from findings in the studies in Taiwan and America, where it was found out that traditional media such as TV was the most preferred source of information because it can be trusted (Ali et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020). This is not surprising since the internet and social media have been in the past implicated in spreading false information. Therefore, people would rather get information from health workers whom they trust. As postulated by Mackworth-Young et al. (2020) in their assessment of community perspectives on COVID-19 in Zimbabwe, people are concerned about trusted sources of information.

Zimbabwe Journal of Health Sciences (ZJHS), Volume 1, Issue 1, December 2021

This implies that health workers should be careful about the methods they use to disseminate COVID-19 information and ensure that trust is created.

In terms of the relationship between risk perception and socio-demographic variables, this study found out that age group, place of residence and sex was significantly associated with risk perception. Similarly, Asefa et al. (2020) and Luo et al. (2020) noted that risk perception significantly varies by socio-demographic variables.

Our study had some limitation too. Due to the cross-sectional nature of this study, it was not possible to assess how risk perceptions change over time. Furthermore, the temporal relationship between risk perception and other variables could not be established. Data collection was also limited to people who had access to the Bulawayo City Council Facebook platform, therefore, the views of those adults who could not access the internet may not have been represented.

Conclusions and recommendations

Higher level of risk perception was found regarding the COVID-19 among adult residents of the City of Bulawayo. The risk perception was significant, especially with age, place of residence and sex. There was immense knowledge of COVID-19 and the most preferred sources of information were health workers and traditional media (i.e., radio and TV). Proper risk communication to promote protective behaviours using health workers and traditional media is thus very essential because these are the sources that the residents of Bulawayo trust. It would be of paramount importance to continuously assess the risk perception at another interval since the perception of risk changes according to the intensity of the outbreak

References

COVID-19 cases worldwide by day | Statista (no date). Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1103040/cumulative-coronavirus- covid19-cases-number-worldwide-by-day/ (Accessed: 15 January 2021

Ali, S. H. et al. (2020) ‘Trends and predictors of COVID-19 information sources and their relationship with knowledge and beliefs related to the pandemic: Nationwide cross-sectional study’, JMIR Public Health and Surveillance. JMIR Publications Inc., 6(4). doi: 10.2196/21071.

Asefa, A. et al. (2020) ‘ Risk Perception Towards COVID-19 and Its Associated Factors Among Waiters in Selected Towns of Southwest Ethiopia ’, Risk

Zimbabwe Journal of Health Sciences (ZJHS), Volume 1, Issue 1, December 2021

Management and Healthcare Policy. Dove Medical Press Ltd, Volume 13, pp. 2601– 2610. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S276257.

Barrios, J. and Hochberg, Y. (2020) Risk Perception Through the Lens of Politics in the Time of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Cambridge, MA. doi: 10.3386/w27008.

Cori, L. et al. (2020) ‘Risk Perception and COVID-19’, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. MDPI AG, 17(9), p. 3114. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17093114.

Dryhurst, S. et al. (2020) ‘Risk perceptions of COVID-19 around the world’, Journal of Risk Research. Routledge, 23(7–8), pp. 994–1006. doi: 10.1080/13669877.2020.1758193.

Gerhold, L. (2020) ‘COVID-19: Risk perception and Coping strategies.’ PsyArXiv. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/xmpk4.

Gorina, M., Limonero, J. T. and Álvarez, M. (2018) ‘Effectiveness of primary healthcare educational interventions undertaken by nurses to improve chronic disease management in patients with diabetes mellitus, hypertension and hypercholesterolemia: A systematic review’, International Journal of Nursing Studies. Pergamon, 86, pp. 139–150. doi: 10.1016/J.IJNURSTU.2018.06.016.

Kwok, K. O. et al. (2020) ‘Community responses during the early phase of the COVID- 19 epidemic in Hong Kong: risk perception, information exposure and preventive measures’, medRxiv. medRxiv, p. 2020.02.26.20028217. doi: 10.1101/2020.02.26.20028217.

Lohiniva, A.-L. et al. (2020) ‘Understanding coronavirus disease (COVID-19) risk perceptions among the public to enhance risk communication efforts: a practical approach for outbreaks, Finland, February 2020’, Eurosurveillance. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), 25(13), p. 2000317. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.13.2000317.

Luo, Y. et al. (2020) ‘Factors influencing health behaviours during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in China: an extended information-motivation-behaviour skills model’, Public Health. Elsevier B.V., 185, pp. 298–305. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2020.06.057.

Mackworth-Young, C. R. et al. (no date) Community perspectives on the COVID-19 response, Zimbabwe.

Mcleroy, K. R. et al. (1988) ‘An Ecological Perspective on Health Promotion Programs’, Health Education & Behaviour, 15(4), pp. 351–377. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500401.

Motta Zanin, G. et al. (2020) ‘A preliminary evaluation of the public risk perception related to the COVID-19 health emergency in italy’, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. MDPI AG, 17(9), p. 3024. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17093024.

Qian, D. and Li, O. (2020) ‘The Relationship between Risk Event Involvement and Risk Perception during the COVID-19 Outbreak in China’, Applied Psychology: Health

Zimbabwe Journal of Health Sciences (ZJHS), Volume 1, Issue 1, December 2021

and Well-Being. Wiley-Blackwell, 12(4), pp. 983–999. doi: 10.1111/aphw.12219.

Rohrmann, B. (no date) RISK PERCEPTION, RISK ATTITUDE, RISK COMMUNICATION, RISK MANAGEMENT: A CONCEPTUAL APPRAISAL.

Roser, M. et al. (2020) ‘Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19)’, Our World in Data. Available at: https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus (Accessed: 15 January 2021).

Wang, P. W. et al. (2020) ‘COVID-19-Related Information Sources and the Relationship with Confidence in People Coping with COVID-19: Facebook Survey Study in Taiwan’, Journal of Medical Internet Research. JMIR Publications Inc. doi: 10.2196/20021.

Wise, T. et al. (2020) ‘Changes in risk perception and protective behaviour during the first week of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States’. PsyArXiv. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/dz428.

Zimbabwe: WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard | WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard (no date). Available at: https://covid19.who.int/region/afro/country/zw (Accessed: 8 March 2021).